In this article I will try to explain the basic engineering that limits graphics card coolers. I will go through the basics of heat transfer, the basics of fluid mechanics and some basic math/physics to explain the 'Blower coolers are bad' paradigm.

A word on blower vs axial coolers, a response.

I recently tried to explain the physics behind what the limitations of blower coolers compared to axial coolers are in a thread and don’t want this answer to get buried … so I’m posting it as a separate post here.

First, we

need to establish what heat/energy transfer even is and what factors play a

role in how much heat/energy can be dissipated by a cooler. To show this I’ll

first explain the general concept of a transport equation.

Something

being transported = coefficient * characteristics of a transport medium/area of effect *

driving force

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let’s look

at what path our energy or heat is going to take and through which layers it

needs to pass through

The hottest

point is going to be the chip itself since it is the heat source.

On top of

the chip is a very thin layer of thermally conductive paste, liquid metal or a

graphite pad. If we look at the packaging of thermal paste, we will find a performance

rating on it stating a number and W/mK which is a rating for thermal

conductivity. A high number means high conductivity which is good for a cooler.

Thermal paste usually has a thermal conductivity between 2 and 15 W/mK, compare

that to copper which has a thermal conductivity between 240 and 380 W/mK. Just

by comparing those two numbers we can already see that it is beneficial to use

as thin a layer of thermal paste because its conductivity is way worse compared

to copper.

Next the

heat/energy must pass through either A) a heat spreader or B) directly into the

heat pipes / vapour chamber.

A heat

spreader is nothing but a plate of copper with the purpose of increasing the

surface area of the hot spot. Therefore, the name heat spreader, it quite

literally spreads thermal energy.

A heat pipe

or vapour chamber both use

There are two types of transport that we will look at today. Thermal conduction and thermal advection.

Thermal conduction is the transfer of heat between atoms next to each other whereas thermal advection is tracking the properties of a fluid while it is moving. Both describe heat exchange and both will be needed to describe the basics of coolers.

Using advection to determine the power draw or cooling power of a cooler is quite easy. All you need to do is to measure how much fluid (air in our case) passes through the cooler to determine the massflow. This can be achived with an aneometer and the known denisity of the air at the measured temperatre. Speaking of temperature, we also need to measure the intake temperature as well as the exhaust temperature. The only information that is missing now is heat capacity (assuming constant pressure).

If we now arrange all of our variables in terms of a transport equation we get the following

Energy transferred to the medium = massflow of air * heat capacity of air * temperature difference between the intake and exhaust

or

Q = m * cp * dT

Now that we know how much energy we can dissipate we therefore know how much energy needs to be conducted through the cooler itself. Heat conduction follows Fourier's Law and can be easily explained when you imagine an iron rod.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There are two types of transport that we will look at today. Thermal conduction and thermal advection.

Thermal conduction is the transfer of heat between atoms next to each other whereas thermal advection is tracking the properties of a fluid while it is moving. Both describe heat exchange and both will be needed to describe the basics of coolers.

Using advection to determine the power draw or cooling power of a cooler is quite easy. All you need to do is to measure how much fluid (air in our case) passes through the cooler to determine the massflow. This can be achived with an aneometer and the known denisity of the air at the measured temperatre. Speaking of temperature, we also need to measure the intake temperature as well as the exhaust temperature. The only information that is missing now is heat capacity (assuming constant pressure).

If we now arrange all of our variables in terms of a transport equation we get the following

Energy transferred to the medium = massflow of air * heat capacity of air * temperature difference between the intake and exhaust

or

Q = m * cp * dT

Now that we know how much energy we can dissipate we therefore know how much energy needs to be conducted through the cooler itself. Heat conduction follows Fourier's Law and can be easily explained when you imagine an iron rod.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Energy

transferred = coefficient of heat transfer * area or a mass flow being heated

(air in our case) * delta temperature

q = a * m

or A * dT

a: (or

alpha depending on the application) This coefficient is a sum of different heat

transfer coefficients, mainly:

- Thermal conductivity of thermal paste and it's thickness

- Thermal conductivity of the material that the vapour chamber is made from

- Heat transfer coefficient between copper and air under turbulent conditions (Pr - Prandtl number etc.)

m: mass

flow rate aka the amount of air that is moved

dT: Delta Temperature between the chip temperature and the environment temperature.

Now that we

have established the main factors that limit us in heat transfer, let's look at

what those do for us.

- a: The higher the coefficient of heat transfer, the better the performance of the cooler (somewhat independent of the fan speed).

- m: The higher the mass flow, the smaller the temperature difference and the higher our chip can clock.

- dT: The higher the temperature difference the more thermal energy is dissipated but we don't really want that because our chip would throttle.

Let's look

at what characterises a radial fan:

- high static pressure

- low air flow rates

Due to the low

air flow rates compared to an axial fan (low static pressure, high air flow)

the blower style cooler is already at a disadvantage in a scenario where fin density or flow resistance isn't the limiting factor.

Now let's

look at how the air flows, aka the direction of the flow:

- In a cooler, that is driven by an axial fan, the air has to only make it through a maximum of maybe an inch (2.54cm) of channelled flow aka known as a radiator.

- in a cooler driven by a radial fan, the air has to travel through the whole heat sink which is 3-4 inches (8-10 cm) ? long.

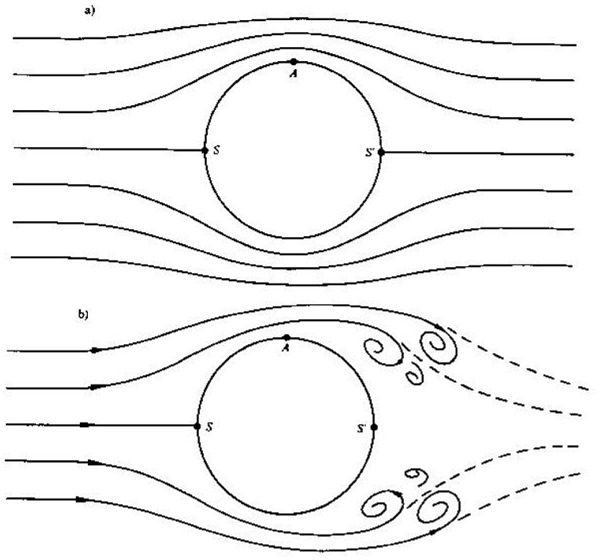

Considering

the fluid velocity in those vapour chamber coolers and the fin density, it seems

reasonable to assume that there will be laminar flow conditions after roughly 3-10x the width

of the fins of the vapour chamber (because of the walls aka no slip condition).

At this

point, heat transfer will get immensely worse because the already hot air is

staying near the copper fins whereas the still colder air travels through the

middle of the fins.

2 dimensional Poiseuille flow:

2 dimensional Poiseuille flow:

|

| Flow profiles ranging from ideal Poiseuille flow to plug flow like |

This

wouldn't be too bad if it was only 2 dimensional, but our world is 3

dimensional and there are 3 or 4 sites (left fin, right fin, vapour chamber

bottom, top shroud) that give the air a hard time getting exchanged.

This is

especially bad since the hottest part of the cooler is at the bottom where 3

sides meet. This air at the bottom gets exchanged slowly compared to further up

the fins where the impact of the bottom surface is negligible (I guess around

2-3 times the fin distance in height). This is the reason why old cooler designs

were mostly limited to 1 slot designs where they would just 'cut the

inefficient top part of the cooler' off.

Or, if you

prefer a more modern design, the Galax GeForce GTX 1070 Katana is a single slot cooler capable of dissipating 150W of heat.

We can see

that a 150W card can be cooled by a single slot cooler because it forces more

air closer to the vapour chamber through the fins.

What I

tried to say with this whole wall of text is: This design doesn't scale well in

height and length.

Higher fins

don't help because heat transfer through the fin itself is linear and the

higher the fin, the cooler the temperature at a certain point.

It also

doesn't help to make it longer because the heat exchange doesn't improve with

length if the air is either a) already at max temperature or b) the no slip

condition is more dominant than the turbulence.

Now that

you know the basics of heat exchange in a cooler, it should also help you to

understand why heat sinks in laptops

are mostly pretty wide, not very tall and show short channel length

Compare

that to a cooler with an axial fan. There you have 4-6 heat pipes that can be

viewed as vapour chambers with 2 *

diameter * length as area ( only 2* diameter and not the circumference because

heat exchange at the point where the air hits the heat pipe and leaves the

heat pipe is pretty low.

Now add to

this the surface area increase provided by the fins (don't forget to consider

the same flow limitations as before) and the increased air flow provided by

axial coolers and you just made yourself a nice explanation why vapour chambers

are not always ideal. :)

Don't be

too harsh on me, English isn't my mother tongue.